Helen & Dave Edwards: Becoming Synthetic

A lecture on Becoming Synthetic: What AI Is Doing To Us, Not Just For Us.

AI is reshaping how students think and learn. The one course every university should teach? Training in cognitive sovereignty—how to collaborate with AI without losing what makes thinking human.

A new Stanford study, Canaries in the Coal Mine, finds that employment for young workers has already fallen 13% in AI-exposed jobs. The researchers identify the core problem: AI replaces "codified knowledge" that forms the foundation of formal education, while experienced workers retain "tacit knowledge" that's harder to automate. Students are being educated and assessed on exactly the knowledge that AI systems already possess.

AI use in college forces educators to confront long-standing tensions around credentialing and assessment. If universities exist merely to transfer information students can get instantly from AI, we're training them for obsolescence.

Students feel this displacement viscerally while simultaneously embracing AI for everything from writing assignments to problem-solving to daily decision-making. Universities label most AI use as academic dishonesty when not explicitly permitted, yet people continue integrating these systems into their thinking processes. Rather than treating this as widespread cheating, we need frameworks for understanding what it means that AI is becoming part of how people think and learn.

When Lori Santos created Yale's happiness course, she addressed a psychological crisis hiding behind academic success. Students needed explicit training in practices their culture had stopped teaching. Similarly, students today need explicit training in cognitive sovereignty—learning to maintain intellectual agency while working symbiotically with AI.

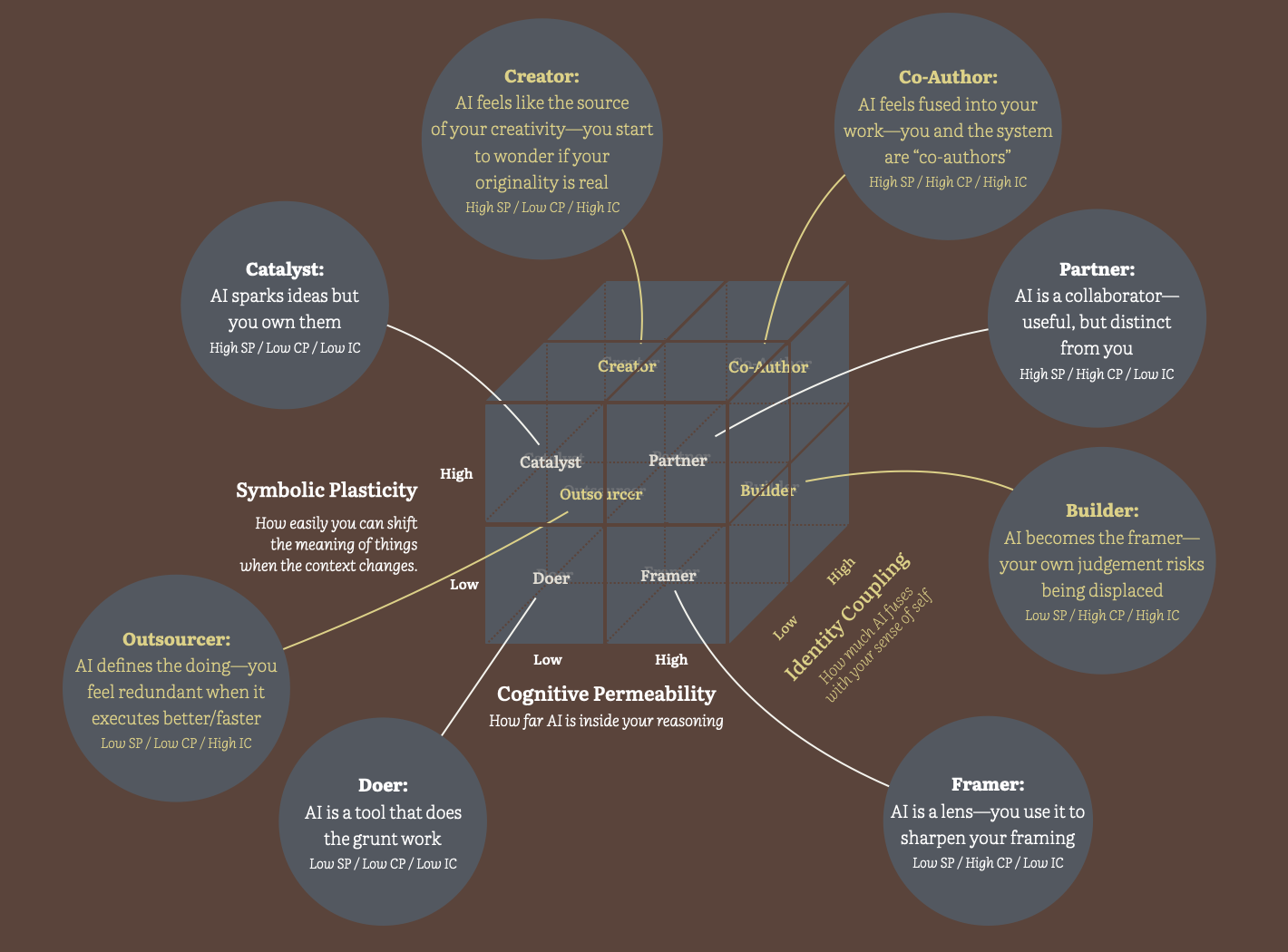

Our research with over 1,000 people adapting to AI reveals how this crisis manifests through changing relationships with thinking itself. We observe three psychological orientations that shape AI relationships: how far AI extends into their reasoning (Cognitive Permeability), how closely their identity becomes entangled with AI interaction (Identity Coupling), and their capacity to shift the meaning of things when context changes (Symbolic Plasticity).

These orientations influence how people assign AI different roles in their cognitive processes, creating eight distinct roles for AI based on their thinking, identity, and meaning-making stance:

This progression moves from simple tool use (Doer) through increasingly complex collaboration, ending with the most sophisticated form of AI partnership (Co-Author). However, sophistication doesn't equal safety in educational contexts. The most problematic pattern for learning is Outsourcer, where low Symbolic Plasticity prevents students from consciously navigating high Identity Coupling. Students develop a sense of professional identity—seeing themselves as researchers, writers, or analysts—that far exceeds their actual capabilities. They couple their identity with outcomes they didn't produce, creating a dangerous gap between self-perception and genuine competence that universities have a responsibility to prevent.

Here's the thing: the same AI interaction can strengthen or weaken thinking depending entirely on which role AI plays in the cognitive process. And while all these roles have implications for learning, the Outsourcer role deserves particular attention because it creates a unique psychological trap in educational settings. Unlike other roles where students maintain some cognitive engagement, Outsourcer eliminates human thinking while creating false competence.

When students assign AI the Outsourcer role for tasks designed to build foundational thinking—having AI write their analysis of complex texts or solve their problem sets—they miss the cognitive struggle that creates understanding. They get correct answers while their reasoning muscles atrophy. A student who puts AI in the Outsourcer role for research synthesis never learns to see patterns across sources or hold multiple perspectives in tension. Worse, they may believe they're developing as a researcher while actually learning nothing about what research synthesis involves or why it matters for generating new insights.

Consider mathematical problem-solving, where universities aim to build quantitative reasoning capacity. When students assign AI the Outsourcer role for calculus homework, they may receive perfect scores while developing no understanding of mathematical concepts, no intuition for when different approaches apply, and no satisfaction from the insight that motivates deeper engagement with mathematics. They think of themselves as "good at math" based on their grades, while having learned nothing about mathematical thinking. The efficiency mindset—getting homework done quickly and accurately—directly undermines the developmental purpose the assignments were designed to serve.

This matters because certain forms of learning require internal cognitive development that can't be distributed to external systems. Memorizing poetry builds neural pathways essential for later metaphorical thinking and creative recombination. Learning to hold complex problems in working memory develops cognitive architecture that enables breakthrough insights years later. When students assign AI the Outsourcer role for these developmental tasks, they skip the cognitive construction that makes advanced thinking possible.

Contrast AI as Outsourcer with AI as Builder in a learning environment. While students who use AI as Builder actively engage with AI reasoning to expand their existing knowledge, students who assign AI as Outsourcer eliminate themselves from the thinking process entirely while believing they're developing expertise.

The Builder role involves real intellectual work (evaluating, integrating, building understanding), even if the student isn't fully aware of how AI is influencing their cognitive process. Outsourcer involves no intellectual work while creating a false sense of progress and competence (unlike Doer, where automation doesn't affect identity).

Yet some AI roles serve learning powerfully. Students who assign AI the Catalyst role—having AI expose gaps in their thinking, then pursuing those gaps independently—can develop stronger reasoning than pure individual effort produces. Putting AI in the Framer role—having AI clarify the boundaries and stakes of a problem before tackling it alone—can accelerate genuine understanding. The same AI system can strengthen or weaken student thinking depending on which role the student assigns it in their learning process.

We believe universities need to distinguish between two fundamentally different educational purposes that have traditionally been bundled together: developing human cognitive capacity (and along with that, identity) and efficiently completing knowledge work.

Cognitive development requires internal struggle, repeated practice, and the satisfaction of emerging capability. Students need to build reasoning muscles, creative frameworks, and intellectual confidence through direct engagement with challenging material. This developmental work can't be outsourced without undermining the purpose.

Knowledge work—research, analysis, document creation—can often benefit from AI collaboration. Students can engage with more sophisticated ideas when AI handles information synthesis, translation between concepts, and mechanical execution. AI as Partner or Builder enables students to tackle problems beyond their current individual capacity.

Universities must help students learn to assign AI different roles based on what they're trying to develop versus what they're trying to accomplish. When the goal is building mathematical reasoning capacity, students need AI to work as a Creator, doing the cognitive work themselves. When the goal is analyzing complex datasets, AI as Partner may enable deeper insights than individual effort alone.

Efficiency and development often require opposing approaches. The fastest way to complete an assignment may undermine the learning it was designed to create. Students need frameworks for choosing when to prioritize growth over speed, when to embrace struggle over convenience.

Every university should require a course—call it "Intelligence in Partnership" or "Thinking in the Age of AI"—that helps students navigate the psychological challenges of human-AI collaboration. Like Santos' "Psychology and the Good Life," this wouldn't be about technical skills but about developing the flexibility to consciously choose how AI fits into people's thinking across different contexts.

The course would teach students to recognize when they're drifting into cognitive dependency versus when they're genuinely collaborating, how to maintain their intellectual voice while leveraging AI capabilities, and how to rebuild their understanding of creativity and expertise when traditional boundaries no longer apply. Students would learn to notice the difference between using AI to enhance their thinking versus letting AI replace their thinking—developing what we call the capacity for conscious partnership in an era when the lines between human and artificial intelligence are increasingly blurred.

The structure of the course would be around practical workshops where students experiment with different AI roles across real academic work. Have them complete the same complex analysis task using AI as Creator (doing all reasoning independently), Catalyst (using AI to spark ideas they develop alone), Partner (collaborating throughout), and Doer (delegating it all to AI). Then reflect: Which role produced the best outcome? What are the differences in the workflows? Which felt most authentic to their learning goals? When did they feel intellectually engaged versus passive? How do different AI roles impact group work and collaboration? What makes them feel more like themselves? What gave them "superpowers" in real-life ways?

Students would develop personal protocols for AI relationship management. When researching for a thesis, use AI as Framer to understand the landscape, Catalyst to generate research questions, but work as Creator when developing their unique theoretical contribution. When learning new material, use AI as Partner for explaining difficult concepts, but work as Creator when practicing application to build genuine competency. Avoid AI entirely when building core skills that require cognitive struggle—memorizing foundational knowledge, developing personal voice in writing, or working through problems that build mathematical intuition. The goal becomes conscious choice about when AI enhances learning versus when it undermines the developmental work universities exist to foster.

Like Santos' happiness course, this is about social and self-awareness, only with AI. Students would learn to notice when they reach for AI before forming their own thoughts, develop comfort with intellectual uncertainty that AI can't resolve, practice the sustained attention that learning requires. They would experience how different AI interactions affect their comprehension, creativity, and sense of authentic capability.

Santos gave students language for psychological experiences they were having but couldn't name—the emptiness behind achievement, the anxiety of constant comparison, the confusion about what actually creates wellbeing. Similarly, students are already experiencing cognitive changes from AI interaction—feeling "hollow" after AI-assisted work, questioning their own capabilities, uncertainty about intellectual authenticity—but they lack frameworks for understanding these shifts. The course would name and address psychological territory students are already navigating, giving them tools for conscious participation rather than unconscious drift.

The commercial stakes make this urgent. AI systems with persistent memory create profound user dependency as students spend months training their AI about their work patterns, interests, and thinking processes. Students who graduate without conscious frameworks for AI relationships become cognitively dependent on whatever systems their employers provide. Imagine the first generation of students who lose their externalized "memory"—years of research notes, creative processes, and intellectual development—when they lose their .edu email access. This creates a new form of cognitive lock-in, where switching systems means losing part of your extended mind.

The crisis extends beyond individual students to collective intelligence. Universities train people who will make decisions affecting millions—in medicine, law, policy, business, education. If these future leaders develop unconscious AI dependencies during their education, they may lose the capacity for independent judgment exactly when society needs clear thinking about AI's role in human institutions.

The Stanford data shows the cost of failing this generation. Students face displacement not because they lack intelligence, but because they were educated to compete with AI on AI's terms—retrieving and processing information faster and more accurately than human minds can manage.

The alternative requires universities to reclaim their foundational purpose: developing people who can think clearly, create meaningfully, and act with wisdom in uncertain conditions. Students who learn to direct AI collaboration while maintaining intellectual sovereignty will have profound advantages over those who drift into cognitive dependency. They'll preserve the human capacities that remain irreplaceable: judgment under uncertainty, creative synthesis, empathetic understanding, and the ability to find meaning in struggle itself.

The question facing every university is whether they'll prepare students for a future where human intelligence is diminished by AI assistance or enhanced through conscious collaboration. The course we've outlined teaches the most essential skill of the AI age: how to think alongside synthetic intelligence without losing what makes thinking human.

Note: Yes, we have developed this course and are pursuing an institution or institutions that are interested in offering it. We are also pursuing philanthropic support to make this course available across the higher education system, including universities, colleges, and community colleges. Please reach out if you are interested in partnering and/or supporting this program by emailing hello@artificialityinstitute.org.